Families Helping Us Grow Into Strong Individuals Showing Percentages

Gimmicky debates about parenthood often focus on parenting philosophies: Are kids ameliorate off with helicopter parents or a free-range approach? What's more than beneficial in the long run, the high expectations of a tiger mom or the nurturing environment where every kid is a winner? Is overscheduling going to damage a child or assistance the child get into a proficient college? While these debates may resonate with some parents, they often overlook the more than bones, central challenges many parents face – particularly those with lower incomes. A broad, demographically based look at the mural of American families reveals stark parenting divides linked less to philosophies or values and more to economic circumstances and changing family construction.

Gimmicky debates about parenthood often focus on parenting philosophies: Are kids ameliorate off with helicopter parents or a free-range approach? What's more than beneficial in the long run, the high expectations of a tiger mom or the nurturing environment where every kid is a winner? Is overscheduling going to damage a child or assistance the child get into a proficient college? While these debates may resonate with some parents, they often overlook the more than bones, central challenges many parents face – particularly those with lower incomes. A broad, demographically based look at the mural of American families reveals stark parenting divides linked less to philosophies or values and more to economic circumstances and changing family construction.

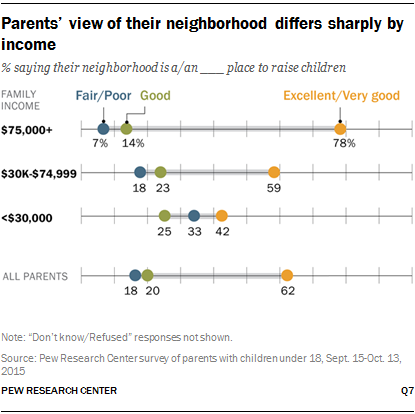

A new Pew Research Center survey conducted Sept. fifteen-October. 13, 2015, among ane,807 U.Due south. parents with children younger than xviii finds that for lower-income parents, financial instability tin can limit their children's access to a prophylactic environment and to the kinds of enrichment activities that affluent parents may have for granted. For example, higher-income parents are virtually twice as likely every bit lower-income parents to rate their neighborhood as an "splendid" or "very practiced" identify to raise kids (78% vs. 42%). On the flip side, a third of parents with annual family incomes less than $thirty,000 say that their neighborhood is only a "fair" or "poor" place to raise kids; simply 7% of parents with incomes in backlog of $75,000 give their neighborhood similarly low ratings.

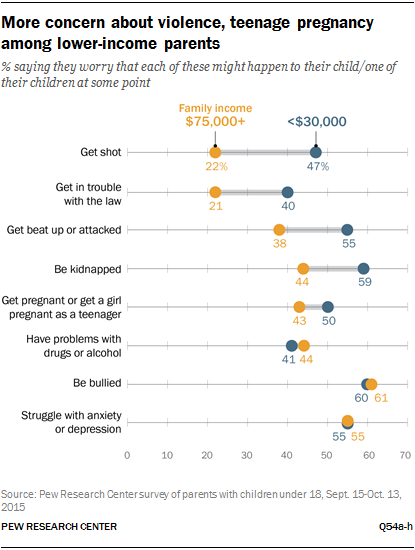

Along with more negative ratings of their neighborhoods, lower-income parents are more likely than those with college incomes to express concerns near their children being victims of violence. At least one-half of parents with family incomes less than $30,000 say they worry that their child or children might be kidnapped (59%) or get vanquish up or attacked (55%), shares that are at to the lowest degree 15 percentage points higher than amidst parents with incomes above $75,000. And about half (47%) of these lower-income parents worry that their children might be shot at some point, more than than double the share among higher-income parents.

Along with more negative ratings of their neighborhoods, lower-income parents are more likely than those with college incomes to express concerns near their children being victims of violence. At least one-half of parents with family incomes less than $30,000 say they worry that their child or children might be kidnapped (59%) or get vanquish up or attacked (55%), shares that are at to the lowest degree 15 percentage points higher than amidst parents with incomes above $75,000. And about half (47%) of these lower-income parents worry that their children might be shot at some point, more than than double the share among higher-income parents.

Concerns about teenage pregnancy and legal problem are as well more prevalent amid lower-income parents. Half of lower-income parents worry that their kid or one of their children will get significant or get a girl significant every bit a teenager, compared with 43% of higher-income parents. And, by a margin of 2-to-1, more lower-income than higher-income parents (forty% vs. 21%) say they worry that their children will get in trouble with the law at some point.

There are some worries, though, that are shared across income groups. At to the lowest degree half of all parents, regardless of income, worry that their children might be bullied or struggle with anxiety or depression at some point. For parents with annual family unit incomes of $75,000 or higher, these concerns trump all others tested in the survey.

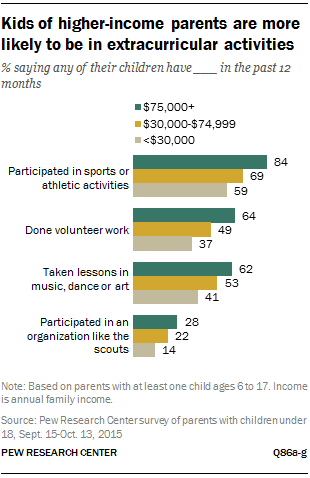

The survey also finds that lower-income parents with schoolhouse-historic period children face more challenges than those with higher incomes when it comes to finding affordable, loftier-quality subsequently-school activities and programs. About half (52%) of those with almanac family unit incomes less than $xxx,000 say these programs are hard to detect in their customs, compared with 29% of those with incomes of $75,000 or higher. And when it comes to the extracurricular activities in which their children participate after school or on weekends, far more higher-income parents than lower-income parents say their children are engaged in sports or organizations such as the scouts or have lessons in music, dance or art. For example, amid loftier-income parents, 84% say their children have participated in sports in the 12 months prior to the survey; this compares with 59% among lower-income parents.

The link between family structure and financial circumstances

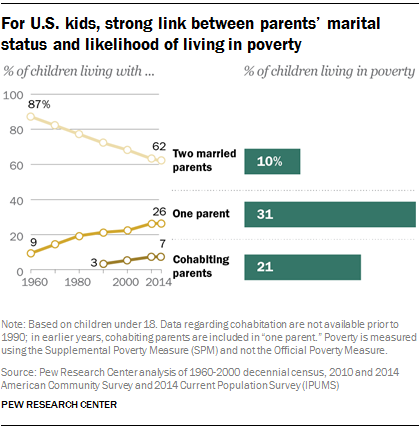

The dramatic changes that accept taken place in family living arrangements have no incertitude contributed to the growing share of children living at the economical margins. In 2014, 62% of children younger than xviii lived in a household with two married parents – a celebrated low, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of data from the U.S. Demography Bureau. The share of U.South. kids living with merely one parent stood at 26% in 2014. And the share in households with two parents who are living together but non married (7%) has risen steadily in recent years.i

The dramatic changes that accept taken place in family living arrangements have no incertitude contributed to the growing share of children living at the economical margins. In 2014, 62% of children younger than xviii lived in a household with two married parents – a celebrated low, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of data from the U.S. Demography Bureau. The share of U.South. kids living with merely one parent stood at 26% in 2014. And the share in households with two parents who are living together but non married (7%) has risen steadily in recent years.i

These patterns differ sharply across racial and ethnic groups. Big majorities of white (72%) and Asian-American (82%) children are living with 2 married parents, as are 55% of Hispanic children. By contrast only 31% of blackness children are living with ii married parents, while more than one-half (54%) are living in a unmarried-parent household.

The economical outcomes for these different types of families vary dramatically. In 2014, 31% of children living in single-parent households were living beneath the poverty line, as were 21% of children living with two cohabiting parents.2 By dissimilarity, simply ane-in-ten children living with two married parents were in this circumstance. In fact, more than half (57%) of those living with married parents were in households with incomes at to the lowest degree 200% in a higher place the poverty line, compared with but 21% of those living in unmarried-parent households.

About parents say they're doing a expert job raising their kids

Beyond income groups, however, parents agree on one matter: They're doing a fine chore raising their children. Most identical shares of parents with incomes of $75,000 or higher (46%), $30,000 to $74,999 (44%) and less than $thirty,000 (46%) say they are doing a very good job as parents, and similar shares say they are doing a practiced task.

Beyond income groups, however, parents agree on one matter: They're doing a fine chore raising their children. Most identical shares of parents with incomes of $75,000 or higher (46%), $30,000 to $74,999 (44%) and less than $thirty,000 (46%) say they are doing a very good job as parents, and similar shares say they are doing a practiced task.

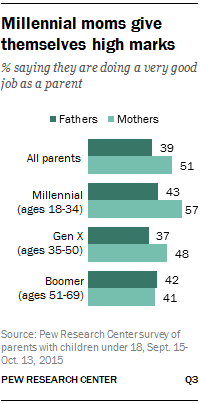

Though parental scorecards don't differ past income, they do vary across other demographic divides, such as gender and generation. Among all parents, more than mothers than fathers say they are doing a very good task raising their children (51% vs. 39%), and Millennial mothers are peculiarly inclined to rate themselves positively. Nearly six-in-ten (57%) moms ages 18 to 34 say they are doing a very skilful job as a parent, a higher share than Millennial dads (43%) or any other generational group.

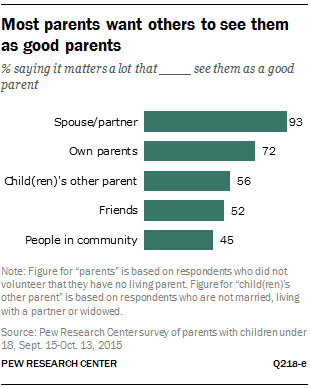

Regardless of how they see themselves, parents care a lot about how others perceive their parenting skills. For married or cohabiting parents, the opinion of their spouse or partner matters the most: 93% of these parents say it matters a lot to them that their spouse or partner sees them as a good parent. But about single parents (56%) also say they care a lot that their child's other parent sees them equally a good parent.

About 7-in-x (72%) parents desire their own parents to retrieve they are doing a practiced job raising their children, and smaller simply substantive shares care a lot that their friends (52%) and people in their customs (45%) come across them as good parents.

About 7-in-x (72%) parents desire their own parents to retrieve they are doing a practiced job raising their children, and smaller simply substantive shares care a lot that their friends (52%) and people in their customs (45%) come across them as good parents.

Parents are nearly evenly divided well-nigh whether their children's successes and failures are more a reflection of how they are doing as parents (46%) or of their children's own strengths and weaknesses (42%). Parents of younger children feel more personally responsible for their children's achievements or lack thereof, while parents of teenagers are much more likely to say that it's their children who are mainly responsible for their own successes and failures.

There are significant differences along racial lines too, with black and Hispanic parents much more than likely than whites to say their children'south successes and failures are mainly a reflection of the job they are doing equally parents.

Mothers are more overprotective than fathers

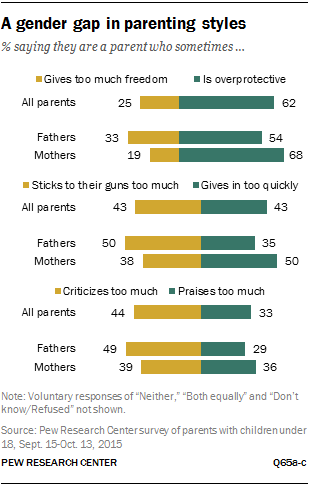

Nigh six-in-ten parents (62%) say they tin sometimes be overprotective, while simply a quarter say they tend to requite their children besides much freedom. More likewise say they criticize their kids too much than say they offer also much praise (44% vs. 33%). American parents are more divided on whether they sometimes "stick to their guns" too much or give in likewise chop-chop (43% each).

In several key means, mothers and fathers approach parenting differently. Mothers are more than likely than fathers to say that they sometimes are overprotective of their children, give in too rapidly and praise their children too much.

In several key means, mothers and fathers approach parenting differently. Mothers are more than likely than fathers to say that they sometimes are overprotective of their children, give in too rapidly and praise their children too much.

Mothers also take more all-encompassing back up networks that they rely on for advice about parenting. They're much more likely than fathers to plow to family members and friends and to take advantage of parenting resources such equally books, magazines and online sources. For example, while 43% of moms say they turn to parenting websites, books or magazines at to the lowest degree sometimes for parenting advice, almost a quarter (23%) of dads exercise the same. And moms are more than than twice as likely every bit dads to say they at least occasionally turn to online bulletin boards, listservs or social media for advice on parenting (21% vs. 9%).

In at least one central area gender does not make a difference: mothers and fathers are as probable to say that being a parent is extremely of import to their overall identity. Well-nigh six-in-ten moms (58%) and dads (57%) say this, and an additional 35% and 37%, respectively, say being a parent is very important to their overall identity.

Parental involvement – how much is besides much?

The survey findings, which affect on different aspects of parenting and family unit life, paint a mixed portrait of American parents when it comes to their involvement in their children's education. Almost one-half (53%) of those with school-age children say they are satisfied with their level of engagement, simply a substantial share (46%) wish they could be doing more. And while parents generally don't recollect children should feel badly virtually getting poor grades as long as they endeavor hard, about one-half (52%) say they would exist very disappointed if their children were average students.

A narrow bulk of parents (54%) say parents can never be too involved in their children's education. But nigh four-in-ten (43%) say too much parental involvement in a child's education can be a bad thing, a view that is particularly mutual among parents with more education and higher incomes. For instance, while majorities of parents with a post-graduate (65%) or a bachelor's (57%) degree say too much involvement could take negative consequences, just 38% of those with some college and 28% with no college experience say the aforementioned.

A narrow bulk of parents (54%) say parents can never be too involved in their children's education. But nigh four-in-ten (43%) say too much parental involvement in a child's education can be a bad thing, a view that is particularly mutual among parents with more education and higher incomes. For instance, while majorities of parents with a post-graduate (65%) or a bachelor's (57%) degree say too much involvement could take negative consequences, just 38% of those with some college and 28% with no college experience say the aforementioned.

Black and Hispanic parents take a much different reaction to this question than exercise white parents, even afterward controlling for differences in educational attainment. Fully 75% of black and 67% of Hispanic parents say a parent can never be likewise involved in a child'southward education. Near half of white parents (47%) concord.

Whether or not they feel too much interest can be a bad thing, a majority of parents are involved – at to the lowest degree to some extent – in their children's education. Amongst parents with school-age children, 85% say they have talked to a instructor about their children's progress in school over the 12 months leading up to the survey. Roughly two-thirds (64%) say they accept attended a PTA meeting or other special school meeting. And threescore% accept helped out with a special project or course trip at their children'due south school. Parents' level of appointment in these activities is fairly consistent across income groups.

Reading aloud is ane way parents can get involved in their children'south education even before formal schooling begins. Amongst parents with children nether the age of half dozen, nearly half (51%) say they read aloud to their children every day, and those who have graduated from college are far more than probable than those who have not to say this is the case. About seven-in-ten (71%) parents with a available'south caste say they read to their young children every day, compared with 47% of those with some college and 33% of those with a high school diploma or less.

Kids are busy, and so are their parents

American children – including preschoolers – participate in a variety of extracurricular activities. At least half of parents with school-age children say their kids accept played sports (73%), participated in religious educational activity or youth groups (60%), taken lessons in music, dance or art (54%) or washed volunteer work (53%) after school or on the weekends in the 12 months preceding the survey.

American children – including preschoolers – participate in a variety of extracurricular activities. At least half of parents with school-age children say their kids accept played sports (73%), participated in religious educational activity or youth groups (60%), taken lessons in music, dance or art (54%) or washed volunteer work (53%) after school or on the weekends in the 12 months preceding the survey.

Among those with children younger than 6, four-in-ten say their immature children have participated in sports, and almost as many say they have been function of an organized play group; one-third say their children have taken music, dance or art lessons.

Parents with annual family incomes of $75,000 or college are far more likely than those with lower incomes to say their children have participated in extracurricular activities. For parents with school-age children, the difference is specially pronounced when information technology comes to doing volunteer work (a 27 percent point difference between those with incomes of $75,000 or higher and those with incomes less than $30,000), participating in sports (25 points), and taking music, dance or art lessons (21 points). Similarly, by double-digit margins, college-income parents with children younger than vi are more likely than those with lower incomes to say their young children have participated in sports or taken dance, music or art lessons in the 12 months prior to the survey.

Parents with college incomes are too more likely to say their children's twenty-four hours-to-solar day schedules are too hectic with besides many things to exercise. Overall, xv% of parents with children between ages half dozen and 17 draw their kids' schedules this fashion. Amongst those with incomes of $75,000 or higher, i-in-five say their children'due south schedules are likewise hectic, compared with 8% of those who earn less than $30,000.

But if kids are busy, their parents are even busier. About 3-in-ten (31%) parents say they always feel rushed, even to practice the things they have to do, and an additional 53% say they sometimes feel rushed. Non surprisingly, parents who feel rushed at least sometimes are more than likely than those who near never feel rushed to meet parenting as tiring and stressful and less likely to see information technology as enjoyable all of the time.

Spanking is an unpopular course of discipline, but one-in-six use it at least sometimes

Parents utilize many methods to discipline their children. The most popular is explaining why a child's beliefs is inappropriate: three-quarters say they do this often. Virtually four-in-ten (43%) say they ofttimes have abroad privileges, such as time with friends or apply of TV or other electronic devices, and a roughly equal share say they give a "timeout" (41% of parents with children younger than 6) as a class of discipline, while about one-in-v (22%) say they often resort to raising their voice or yelling.

Parents utilize many methods to discipline their children. The most popular is explaining why a child's beliefs is inappropriate: three-quarters say they do this often. Virtually four-in-ten (43%) say they ofttimes have abroad privileges, such as time with friends or apply of TV or other electronic devices, and a roughly equal share say they give a "timeout" (41% of parents with children younger than 6) as a class of discipline, while about one-in-v (22%) say they often resort to raising their voice or yelling.

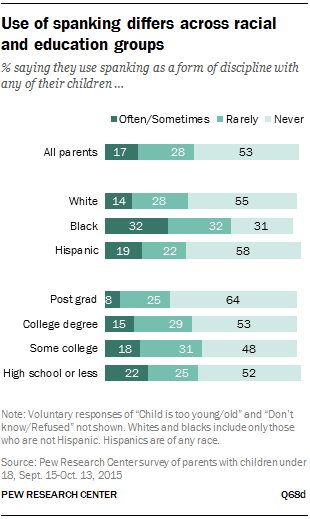

Spanking is the least unremarkably used method of field of study – merely 4% of parents say they practice it oftentimes. Merely ane-in-six parents say they spank their children at least some of the time equally a way to discipline them. Blackness parents (32%) are more likely than white (xiv%) and Hispanic (xix%) parents to say they sometimes spank their children and are far less likely to say they never resort to spanking (31% vs. 55% and 58%, respectively).

Spanking is also correlated with educational attainment. About one-in-v (22%) parents with a high school diploma or less say they use spanking as a method of discipline at least some of the time, as do 18% of parents with some college and fifteen% of parents with a bachelor's degree. In contrast, only 8% of parents with a post-graduate degree say they frequently or sometimes spank their children.

Parental worries differ sharply by race, ethnicity

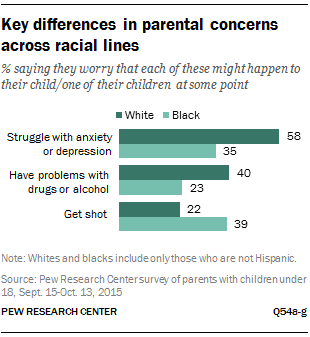

In improver to the economic gaps that underlie parents' worries well-nigh the safe and well-being of their children, broad racial gaps exist on a few key items. White parents are far more than likely than black parents to worry that their kids might struggle with anxiety or depression (58% vs. 35%) or that they might take issues with drugs or alcohol (twoscore% vs. 23%). Black parents, in plough, worry more than than white parents do that their children might get shot at some point. About four-in-10 (39%) black parents say this is a business organization, compared with about ane-in-v (22%) white parents. And this difference persists fifty-fifty when looking at white and black parents who live in urban areas, where there is more concern most shootings.

In improver to the economic gaps that underlie parents' worries well-nigh the safe and well-being of their children, broad racial gaps exist on a few key items. White parents are far more than likely than black parents to worry that their kids might struggle with anxiety or depression (58% vs. 35%) or that they might take issues with drugs or alcohol (twoscore% vs. 23%). Black parents, in plough, worry more than than white parents do that their children might get shot at some point. About four-in-10 (39%) black parents say this is a business organization, compared with about ane-in-v (22%) white parents. And this difference persists fifty-fifty when looking at white and black parents who live in urban areas, where there is more concern most shootings.

On each of these items and others tested in the survey, Hispanic parents are more likely than white and black parents to express concern. These differences are driven, at to the lowest degree in part, by high levels of concern amongst foreign-born Hispanics, who tend to accept lower household incomes and lower levels of educational attainment than native-born Hispanics.

The residual of this study includes an examination of irresolute family structures in the U.South. as well as detailed analyses of findings from the new Pew Research Center survey. Chapter one looks at the changing circumstances in which children are raised, drawing on demographic data, largely from U.Due south. government sources. This assay highlights the extent to which parents' changing marital and relationship condition affects overall family makeup, and it as well includes detailed breakdowns by primal demographic characteristics such every bit race, education and household income. Chapters ii through v explore findings from the new survey, with Chapter ii focusing on parents' assessments of the job they are doing raising their children and their families' living circumstances. Chapter 3 looks at parenting values and philosophies. Chapter iv examines kid care arrangements and parents' involvement in their children'southward education. And Affiliate 5 looks at extracurricular activities.

Other key findings

- About six-in-ten (62%) parents with infants or preschool-historic period children say that it's hard to find child care in their community that is both affordable and high quality, and this is truthful across income groups. Nigh working parents with annual family unit incomes of $75,000 or higher (66%) say their young children are cared for in day care centers or preschools, while those earning less than $thirty,000 rely more heavily on care past family members (57%).

- On average, parents say children should exist at least 10 years old before they should be immune to play in front of their firm unsupervised while an adult is within. Parents say children should be even older before they are allowed to stay home alone for about an hour (12 years old) or to spend fourth dimension at a public park unsupervised (14 years old).

- Roughly a third of parents (31%) with children ages 6 to 17 say they accept helped autobus their child in a sport or athletic activeness in the past year. Fathers (37%) are more probable than mothers (27%) to say they take done this.

- Nine-in-ten parents with children ages half-dozen to 17 say their kids watch TV, movies or videos on a typical day, and 79% say they play video games. Parents whose children get daily screen time are split about whether their children spend too much time on these activities (47%) or about the right corporeality of time (50%).

- Eight-in-10 (81%) parents with children younger than 6 say that their young children sentry videos or play games on an electronic device on a daily footing. Roughly a third (32%) of these parents say their kids spend too much time on these activities; 65% say the amount of time is almost correct.

Throughout this report, references to college graduates or parents with a college degree comprise those with a bachelor'due south caste or more. "Some higher" refers to those with a two-year degree or those who attended college but did not obtain a degree. "High school" refers to those who have attained a high schoolhouse diploma or its equivalent, such as a General Education Development (GED) document.

Mentions of "school-historic period" children refer to those ages 6 to 17. "Teenagers" include children ages xiii to 17.

References to white and blackness parents include simply those who are non-Hispanic. Hispanics are of any race.

Mentions of Millennials include those who were ages eighteen to 34 at the fourth dimension of the survey. Gen Xers are ages 35 to 50. Baby Boomers are ages 51 to 69.

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2015/12/17/parenting-in-america/

0 Response to "Families Helping Us Grow Into Strong Individuals Showing Percentages"

Postar um comentário